Vital Statistics

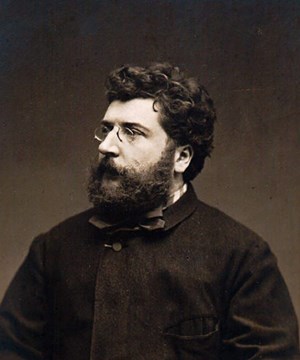

Born: October 25, 1838, Paris

During Lifetime: Railroads helped create the suburbs of Paris. Baron Haussmann redesigned Paris, leveling entire districts and creating the city’s modern face. A new opera house, the Palais Garnier, was built. War with Prussia, in 1871, brought down France’s Second Empire, and 20,000 Parisians died fighting their own government during the Paris Commune.

Biographical Outline

- Young professional, 1860: Bizet works as an arranger, making piano reductions of large scores. In 1863, he writes Les pêcheurs de perles (The pearl fishers) for the Theatre-Lyrique. This is a moderate success winning praise from then-critic Hector Berlioz.

- Doubt, 1867: The lukewarm reaction to Bizet’s La jolie fille de Perth (The fair maid of Perth), troubles Bizet and increases his chronic indecisiveness. Nevertheless, he continues to work, finishing the big symphony Roma in 1868.

- Back on track, 1871-1872: Bizet finishes the one-act opera Djamileh and the piano suite Jeux d’enfants (Children’s games), some of which are orchestrated and performed. The orchestral suite of music to the play L’Arlesienne (The girl from Arles, 1872), is an immediate hit.

- Carmen, 1873-1875: Commissioned by the Opéra Comique. Rehearsals for Carmen are delayed, partly because one of the Opéra Comique’s two directors objected to the morality of the libretto. It finally premieres on March 3, 1875, and is successful, despite its scandalous storyline. Bizet dies three months later, after suffering two heart attacks.

Fun Facts

- Name game: Bizet’s given name was Alexandre César Léopold. He just liked Georges better.

- Dual nature: Bizet was sincere, guileless, and vivacious. However, he was also moody and indecisive, which caused a break in his marriage. A theater composer has to take charge of his librettists and the staging of a work, and deal effectively with theater directors. Bizet could do none of this, floating from project to project without a clear path. That’s a major reason for his theatrical failures.

- Highest praise: Bizet’s ability as a pianist, particularly as a sight-reader, was so great that the famous Liszt pronounced him his equal.

- Parisian to the core: Aside from his three years in Italy after winning the Prix de Rome, Bizet rarely left Paris and its suburbs.

- Recycler: Bizet always reused material from unproduced or unfinished works. That’s a good thing, because Bizet left a lot of unfinished work: Only six of 30 opera projects he started were ever completed.

- Movie life: Carmen is unquestionably one of the most famous and popular operas of all time. There are numerous film versions, including two silent movie versions in 1915, a flamenco version (by Carlos Saura, 1983), and a traditionally operatic version (1984). In 1943, Oscar Hammerstein II wrote an African American version, Carmen Jones, and two recent movie adaptations have been set in Dakar, Senegal (Karmen Gei, sung in Wolof and French) and South Africa (U-Carmen-e-Khayelitsha, 2005, sung in the Xhosa language).

Recommended Biography

There are no recent, English language biographies of Bizet. The standard one is out of print, but is worthwhile, if you can find it:

Mina Stein Kirstein Curtiss, Bizet and His World. (Greenwood Press Reprint, 1977).

Explore the Music

- Melody Man: Bizet had a huge melodic gift. Aside from Carmen, The Pearl Fishers has recently become quite common onstage. Bizet’s other operas are almost never produced. The L’Arlesienne suite is a staple of orchestral programs, along with the Symphony in C Major, written when he was 17. Many of his melodies (art-songs) are brilliant, and Jeux d’enfants is delightful.

- Carmen the great: Bizet’s Carmen is a landmark in 19th-century opera for its grittiness, its defiantly sexual leading female character, and its non-heroic portrayal of a wide slice of society. It is consistently one of the five most performed operas in the world and contains some of the most famous opera melodies ever written, foremost the Habanera and the Toreador Song.

- To sing, or to speak: The dialogue in Carmen was originally meant to be spoken. Recitatives were added by Bizet’s friend Ernest Guiraud after the composer’s death, to help broaden the work’s appeal to producers.

- Misrepresented: Many of Bizet’s original autograph scores are still missing, and his works exist in a variety of unreliable, unauthorized, badly edited versions.

Recommended Websites

-

Wikipedia with few audio files

-

International Music Score Library Project: Free scores of Bizet’s music from a variety of publishers

-

Free music selections from last.fm

Recordings

- Carmen (DVD)

- Anna Caterina Antonacci, Jonas Kaufmann, Ildebrando D’Arcangelo; Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Antonio Pappano cond.; Francesca Zambello, director (Decca 2008)

- Agnes Baltsa, Josè Carreras, Samuel Ramey; Metropolitan Opera House, James Levine, cond.; Paul Mills, director. (Deutsche Gramophon 2007/1987 production)

- Carmen (Compact Disc)

- Both of these recordings feature dialogue instead of sung recitative. However the EMI recording replaces the singers with French actors during those (brief) parts.

- Tatiana Troyanos/ Placido Domingo/ Josè van Dam; London Philharmonic/ Georg Solti (London, 1990)

- Grace Bumbry/ Jon Vickers/ Kostas Paskalis; Orchestra of the National Opera, Paris/ Rafael Fruhbeck de Burgos (EMI, 2004)

- Orchestral Music

- Suites 1 and 2 from L’Arlesienne / Suite from Carmen

- Barcelona Symphony Orchestra/ Josè Serebrier (Bis, 2004). Serebrier’s Carmen Symphony contains all the music from both suites and some extras.

- Les Musiciens du Louvre/ Marc Minkowski (Naïve, 2008). The L’Arlesienne suites are augmented by more of Bizet’s incidental music.

- Symphony in C

- New York Philharmonic/ Leonard Bernstein (Sony, 1999). Also contains music by Offenbach

- Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra/ Bernard Haitink (Eloquence, 2007). Also includes Jeux d’enfants orchestral suite and Saint-Saens’ “Organ” Symphony.

- Songs

- Ann Murray/ Graham Johnson, Songs by Bizet (Hyperion, 1998)

- Cecilia Bartoli/ Myung-Whun Chung, Chant d’Amour (London, 1996)